How to shrink a government department

A ten-step guide

Recently, it was reported that the Government of Canada set a target to reduce program spending by 15% over three years. That’s a big target. But it’s possible. I know, because I led a team that did that at the Government of Alberta.

Before I was an MP, before I worked in higher education, I was a public servant.

From 2016 through 2020, I served as head of Alberta’s cross-government communications department, Communications and Public Engagement (CPE).

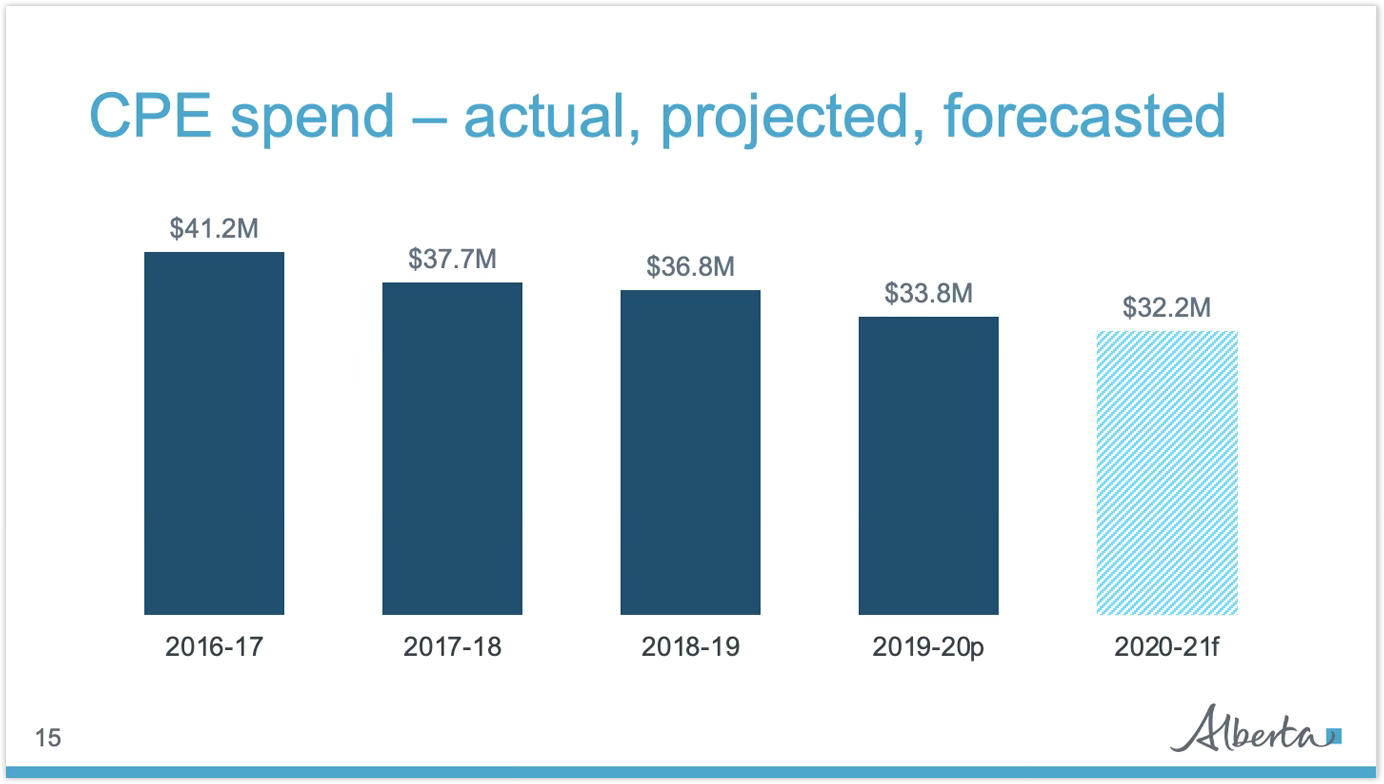

In three years, and with no layoffs, we reduced the size of our budget by 18%, saving $7.4 million a year in the process. That three-year project spanned two premiers – New Democrat Rachel Notley and Conservative Jason Kenney – and had the support of both.

That’s because wanting an efficient public service, one that is careful with money, is not a partisan position. Governments of all stripes – arguably especially governments that believe in the good of government – need to be careful stewards of public dollars and aggressively chase value for the people they serve.

CPE was not the biggest government department (though by no means was it the smallest). But our experience and what we learned (sometimes only after doing it wrong a few times) provides many practical lessons for Ministers, Deputy Ministers, ADMs, Directors-General and all the other public servants in leadership positions across this country.

Here’s ten lessons I think are particularly important:

1. HAVE A PLAN

In the words of Yogi Berra - if you don’t know where you’re going, you might end up somewhere else.

Having a plan might seem obvious, but my experience is that plans are unpopular. Plans require you to choose programs that are winners and programs that are losers – and to act accordingly. Flat cross-department cuts seem much more popular. They seem easy to sell: a Deputy Minister gets to say things like “we’re all in this together” and “I trust local decision-making”.

Similarly, shrinking through not filling vacancies seems popular. Nobody is reassigned and nobody loses their position.

But flat cuts within a department, cutting just where vacancies occur, and cutting only the contracts that come up for renewal are not good strategies and certainly not a plan. You’d have to be incredibly lucky to lose the right positions and the right contracts in the right areas. Success IS possible, but success in such a model is accidental.

More likely, a creeping sense that the department is in drift and decline will set in among your staff. If you don’t change how you work but do change how many people are doing the work, people just have more to do. Everything becomes harder. Resentment spreads: programs that were already efficient feel punished, and the bloated ones feel judged.

Even just reviewing every program in isolation is not, in my opinion, good strategy. You optimize programs but you don’t ask if the programs are what they need to be within a broader context.

So – don’t do that!

There are lots of planning models. My preferred is blank paper: if your department didn’t exist and somebody asked you to create it tomorrow – what services would you offer? Why? How would you structure it? Why?

Once you have that, you know where you’re going. You know which vacancies you fill and which you don’t. You know which verticals to grow, which to maintain, and which to wind down.

The rest is just implementation.

2. COORDINATE YOUR PLAN WITH EVERYBODY ELSE’S PLAN

As you consider the work that needs to be done, consider whether you’re the one that needs to be doing the work.

Don’t be territorial, don’t be an empire builder. The best leaders in the public service are the ones who know their value isn’t in the size of their org chart. It takes incredible confidence in yourself and team to let go – to be able to say to a colleague: “You know what? It’s yours. I trust we can work together on this.”

3. REMEMBER THAT DOLLARS ARE REAL - FTEs ARE NOT

In tighter times, big organizations will often strengthen position control or introduce additional rules around long-term spending and contracting. Departments are often given, in addition to their dollar budget, “Full-Time Equivalency (FTE)” budgets that limit how many staff they can hire, and whether those staff can be permanent or temporary.

Be very careful.

Position control is not an end in its own right. It is a means to save money and reduce long-term risk. I have seen many public servants decide to outsource because they didn’t have the FTE budget, even when it cost more. I’d be lying if I said I never did that.

I’ve also seen the opposite – insourcing when the work could be done cheaper, better and faster (and with less long-term commitment) by contractors, simply because the rules push people that way.

But FTEs aren’t real, nor are contracting restrictions. They serve a purpose, but they are created by government and can be changed by government. Money is real. Outcomes are real. You should make decisions because they save money or improve outcomes. That’s the goal. Don’t get lost in the forest of rules and regulations. Any sensible rules have exemptions for just such cases.

4. INSIST ON CLEAR ACCOUNTABILITIES

In a letter to the public service, new-head-of-public-service Michael Sabia summarized his approach in three words: focus, simplicity, accountability. Certainly, that’s a lot tighter than the 2,000 I’m providing you and I think it’s an incredible roadmap for better services.

I feel like most would think the biggest cost savings come from the first two words – focus and simplicity. My experience is, in government, real savings comes from the third – accountability.

Government is a notoriously soft-power environment. Much of what is done is done through unwritten rules and negotiation – between ministers, between departments, between colleagues whose work deeply overlaps.

It is also a notoriously CYA environment. Recommendations move up chains. People get mad about said recommendations. People get mad the right person wasn’t in the meeting. There is safety in numbers.

All this means a lot of government work is done by committees as opposed to by individuals. A press release is jointly written by six people in a two-hour meeting. A policy recommendation is pitched to a Minister by ten public servants from across four departments.

In most government departments, people’s time – that is, salaries and benefits – is going to be the most expensive line item. A culture of accountability means one person writes a press release, and it takes three hours instead of twelve. It means four public servants brief the minister instead of ten, halving the cost of that activity.

A culture of accountability requires politicians, public service leaders, and public servants across Government to increase their tolerance for being left out of decisions, increase their patience with the decisions that reach their desk and increase their willingness to delegate and trust the teams that report to them – to resist the urge to override.

Accountability is a much bigger ask than it seems. But accountability is one of the most powerful tools available to reduce public service workloads and – in turn – the size and cost of government.

5. IF YOU ARE LEANING UP AREAS, BE INCREMENTAL

In business school, I had an Operations Management instructor who said nobody looks dumber than the person who has run the numbers from a distance and comes in and tells the people on the ground exactly how much they need to cut (or grow) their batch size or staff complement.

His lesson is a good one: precise models are precisely wrong. Every job has an unmeasurable component. Your idea, from the distance of leadership, of how many staff are required for any given task is an approximation at best. If, rather than feeling you need to rethink your business, you simply feel you are overstaffed, reduce staffing gradually (this is a great place for reducing team size through attrition) and carefully watch outcomes.

Be alert to the signs that you might have reached the end of gains. Work closely with the affected team on strategies to manage shifting workload, including encouraging them (and giving them permission) to focus on value-adding work, and deprioritize low value work.

6. IN EVERYTHING ELSE, BE QUICK

For bigger, more fundamental changes, you have to move quickly, especially once it has been communicated as a possibility.

Adopt a mantra: that which will be done eventually, must be done immediately. I promise you, it will not be better when people have had two months to adjust to the thought of future change. It’s two months to fret and not know what their future holds.

You can move so much faster than you think you can.

7. DON’T CHANGE WHAT YOU DON’T UNDERSTAND

Fight the instinct to feel something is useless if you don’t engage with it or understand it. When you don’t understand the usefulness or function of an area is when you need to tread most carefully. “Do not remove a fence until you know why it was put up in the first place.”

And track time – every task. It’s unpopular, but less so than you think, and very common in many sectors (as well as many parts of the federal bureaucracy). Time is the public service’s largest expenditure. You cannot properly weigh the cost of an internal team doing a project vs. alternatives if you don’t know how much time people are working on that project.

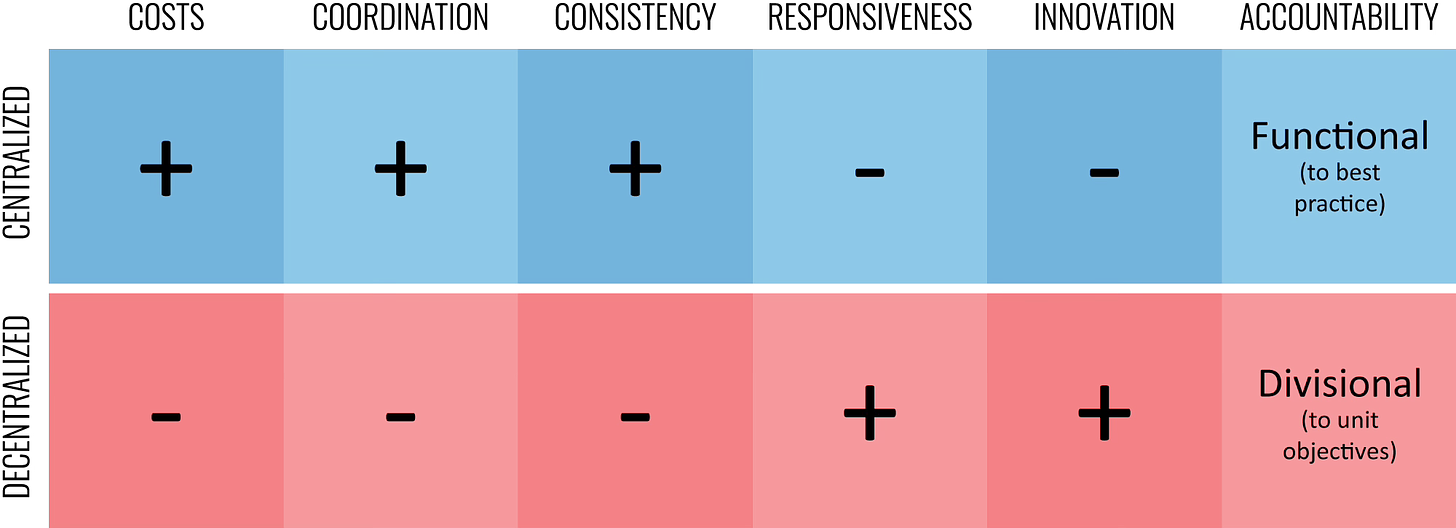

8. CENTRALIZATION IS NOT ALWAYS THE ANSWER

Anyone who has ever worked in a big organization knows how much duplication can occur the minute you have a departmental model. Organizations in search of savings often look to centralize functions.

This makes sense. But central models aren’t perfect.

Both central and distributed models have benefits. Both also have drawbacks. And what tends to happen over time is the benefits of your model get taken for granted and the drawbacks start to dominate your thinking.

So, before you centralize, ask yourself if you might be taking for granted the responsiveness, innovation and local accountability inherent in decentralized models. Also remember that any reorganization of this nature incurs significant change costs, and performance will likely dip for quite some time before you see any of the benefits. Do you have the time? Do you have the patience?

If you do decide to reorg, remember that neither the benefits nor drawbacks of a model are destiny. Build your systems accordingly – and watch their performance.

9. REMEMBER, ANY BIG CHANGE COMES WITH A SHAKEDOWN PERIOD - MAKE SURE YOUR TEAM KNOWS TOO

Change rarely makes things better in the short term.

It’s important to be honest with your team about what change feels like. Things often get harder before they get better. People lose familiar routines, teams get shuffled, and everyone spends more time figuring things out and less time getting things done.

That’s normal.

Keep your overall direction, but embrace that you’ll be making course corrections. Commit to fixing things as they come up and making the transition work. And if it’s clear something will never work, don’t be stubborn. Fail fast.

10. WORK WITH THE UNIONS. THEY’RE OUR PARTNERS, AND WE’RE ALL IN THIS TOGETHER

Efficient government is sustainable government, and sustainable government offers job security. The work the government is doing to reduce costs frees up the fiscal capacity that we need. My experience is such cost saving can be done in a way that maintains the government as an employer of choice and makes life better for workers. It can reduce workloads, it can improve job satisfaction and increase internal job opportunities – and it can be implemented gradually and smartly, in a way that avoids the worst horror stories of government restructurings past and present.

Your odds of doing all that are better when you treat organized labour as a true partner. Engage them early. Listen to their ideas.

In my department, CPE, we managed to reduce costs (18%) while improving client satisfaction (up 19 points to 94%) and increase employee satisfaction to among the highest in the Alberta public service (12 points above average).

We were lucky. This was the marriage of good political leadership, good public service leadership, good union leadership and a team that was willing to work together to fundamentally rethink our business.

It was essential work.

It’s even more essential today, for the Government of Canada. To build, to protect, and to secure this country, it’s going to take money. It’s going to take focus, simplicity and accountability. It’s going to take Government doing things smarter and better than we’ve ever done before. And it’s going to require change.

But now’s the time. Delivering for Canadians has never been more important.

Someone pointed me to a comment on Reddit that it would be easier to cut in communications because we just cut ad spend.

I’m not on Reddit so I’ll just post the answer here - advertising and sponsorship budgets were in the departments we serve and they paid ad costs directly with only very limited exceptions (we had a small budget for social media boosting which actually didn’t exist in the first fiscal year noted - was funded from savings).

The numbers above are the operations of communications, not ads: marketing services, translation services, PR, events, public opinion, consultations, design, media monitoring, web infrastructure and writing, etc.

Great advice for public and any private sector organizations looking for sustainable efficiencies. The credibility of this advice is confirmed by its demonstrated success. This should find its way into a Globe & Mail OpEd piece. Canadians would be impressed and reassured that this government is serious about fundamental, structural change to improve national productivity.